“To know when one's self is interested, is the first condition of interesting other people.”

Fuente: Marius the Epicurean http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext03/8mrs110.txt (1885), Ch. 6

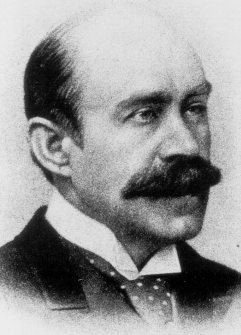

Walter Horatio Pater fue un ensayista inglés, crítico literario, e historiador de arte. En lo profesional fundamentalmente se destacó como profesor en la Universidad de Oxford, y por sus escritos teóricos .

Hijo de un médico que murió cuando Walter era aún un niño, se trasladó luego a Enfield con su familia. Fue alumno y profesor universitario en Oxford, y realizó esporádicos viajes por Francia y Alemania, y mucho más asiduamente por Italia. Alternó la escritura en periódicos y revistas con los cursos que intermitentemente impartió en Oxford.

Consagrado muy especialmente a la estética, de personalidad inquieta y nostálgica, fue discípulo de John Ruskin,[1][2] aunque rechazaba la interpretación moralizante del arte que realizaba este último;[3] también fue maestro de Oscar Wilde.[4][5]

Escribió la novela filosófica, Mario el epicúreo , que impresionó a toda su generación y fue considerada una especie de "Biblia del Esteticismo". En ella plasmó sus ideales estéticos y religiosos a un mismo tiempo. Su héroe, el joven Mario, vive en la época de los Antoninos. Al principio, el cálido culto de los dioses domésticos y de los espíritus campestres colman todas sus aspiraciones, pero la muerte de su madre y de su más querido amigo, el poeta Flavio, lo sumen en la incertidumbre sobre los problemas fundamentales de la vida, que cree resueltos en la filosofía epicúrea. Más tarde, su decisivo encuentro con Marco Aurelio le inclina hacia las doctrinas estoicas. Finalmente es seducido por el espíritu rebelde y la serena actitud fraterna y esperanzada de los fieles que se reúnen en las catacumbas romanas o mueren en el circo. William Butler Yeats llegó a afirmar que el citado fue el único y verdadero libro sagrado para su generación.

Walter Pater destacó, además, en el género del ensayo. Lo ejercitó sobre todo como crítico e historiador de arte. En relación al Renacimiento escribió importantes ensayos. Exceptuando Apreciaciones y Platón y el Platonismo , son justamente famosos y conocidos sus Estudios en la Historia del Renacimiento, escrito que se editó en 1873 y que alcanzó cuatro ediciones más, aunque el texto definitivo sólo encontró su forma en 1893 con un capítulo extra, «La escuela de Giorgione», y con la recuperación de un párrafo que causó el escándalo del obispo de Oxford, porque «invitaba a compensar la brevedad de la vida con la intensidad de alguna exquisita pasión o alguna extraña sensación»:

La pasión poética, el anhelo de belleza y el amor del arte por el arte, poseen en grado sumo esta sabiduría . Pues el arte llega a nosotros con el fin único de aportar a nuestra breve existencia una cualidad sublime, simplemente por amor a ese momento fugaz.

[6]Además del «Prefacio» o «Prólogo», Pater incluyó en El Renacimiento. Estudios de arte y poesía[7] los ensayos «Dos tempranas historias francesas», «Pico della Mirandola»,[8] «Sandro Botticelli»,[9] «Luca della Robbia»,[10] «La poesía de Miguel Ángel»,[11] «Leonardo da Vinci»,[12] «La escuela de Giorgione»,[13] «Joachim de Bellay»,[14] y un muy interesante ensayo sobre «Winckelmann»,[15] además de una conclusión. Las ediciones inglesas modernas también incluyen como apéndice un breve texto de 1864 titulado «Diaphaneité».[16]

Inspirándose en Gotthold Ephraim Lessing y en Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, el intelectual que aquí nos ocupa proponía una flexibilización de los cánones artísticos más clásicos creando uno nuevo: Aquél que atendía en la obra literaria y artística a su cualidad sensible, a la producción de sentimientos y placer estético, a partir de la forma.

La forma unificaba todo el arte, y, como llegó a decir, «todas las artes tienden a la condición de la música, que sólo es forma», y lo que proporciona placer estético, se reduce fundamentalmente a forma. Por eso el arte es autónomo e independiente de todo principio moral, al contrario de lo que afirmaba Ruskin.

Ante la primacía del hedonismo, el artista se crea sus propios valores que no tienen por qué coincidir con lo que la moral victoriana de la época pregonaba.

Escritor de refinado y poético estilo, Walter Pater gozó de una enorme influencia en muchos escritores de su época. En él el helenismo dejó intensos ecos en su concepción estética y en su anhelo de pasión y de luminosidad. Ese amor a lo clásico antiguo orientó toda su crítica y su estética.

Su influencia se dejó sentir en muchos escritores ingleses, como James Joyce o Virginia Woolf. El primero construye sus «epifanías» , como una variante de las «impresiones» que Walter Pater describe en la famosa «Conclusión» de su libro «El Renacimiento». La segunda enuncia una actitud parecida ante la totalidad del presente en la novela «Al Faro», con sus célebres palabras finales: «Ya está, he tenido mi visión».

Walter Horatio Pater ejerció sin duda una notable influencia en la narrativa y la sensibilidad modernas.

Wikipedia

“To know when one's self is interested, is the first condition of interesting other people.”

Fuente: Marius the Epicurean http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext03/8mrs110.txt (1885), Ch. 6

“Not the fruit of experience, but experience itself, is the end.”

Conclusion

The Renaissance http://www.authorama.com/renaissance-1.html (1873)

Contexto: Not the fruit of experience, but experience itself, is the end. A counted number of pulses only is given to us of a variegated, dramatic life. How may we see in them all that is to to be seen in them by the finest senses? How shall we pass most swiftly from point to point, and be present always at the focus where the greatest number of vital forces unite in their purest energy. To burn always with this hard, gem-like flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life.

Conclusion

The Renaissance http://www.authorama.com/renaissance-1.html (1873)

Contexto: Not the fruit of experience, but experience itself, is the end. A counted number of pulses only is given to us of a variegated, dramatic life. How may we see in them all that is to to be seen in them by the finest senses? How shall we pass most swiftly from point to point, and be present always at the focus where the greatest number of vital forces unite in their purest energy. To burn always with this hard, gem-like flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life.

Pico Della Mirandola

The Renaissance http://www.authorama.com/renaissance-1.html (1873)

Fuente: Marius the Epicurean http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext03/8mrs110.txt (1885), Ch. 6

“It is the addition of strangeness to beauty that constitutes the romantic character in art.”

Appreciation, Postscript (1889)

Fuente: Marius the Epicurean http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext03/8mrs110.txt (1885), Ch. 25

On the Mona Lisa, in Leonardo da Vinci

The Renaissance http://www.authorama.com/renaissance-1.html (1873)

“What we have to do is to be forever curiously testing new opinions and courting new impressions.”

Conclusion

The Renaissance http://www.authorama.com/renaissance-1.html (1873)

Conclusion

The Renaissance http://www.authorama.com/renaissance-1.html (1873)

Conclusion

The Renaissance http://www.authorama.com/renaissance-1.html (1873)