Fuente: Rhetoric as Philosophy (1980), pp. 31-32

Contexto: In the second part of the Phaedrus Plato attempts to clarify the nature of “true” rhetoric. … it does not arise from a posterior unity which presupposes the duality of ratio and passio, but illuminates and influences the passions through its original, imaginative characters. Thus philosophy is not a posterior synthesis of pathos and logos but the original unity of the two under the power of the original archai. Plato sees true rhetoric as psychology which can fulfill its truly “moving” function only if it masters original images [eide]. Thus the true philosophy is rhetoric, and the true rhetoric is philosophy, a philosophy which does not need an “external” rhetoric to convince, and a rhetoric that does not need an “external” content of verity.

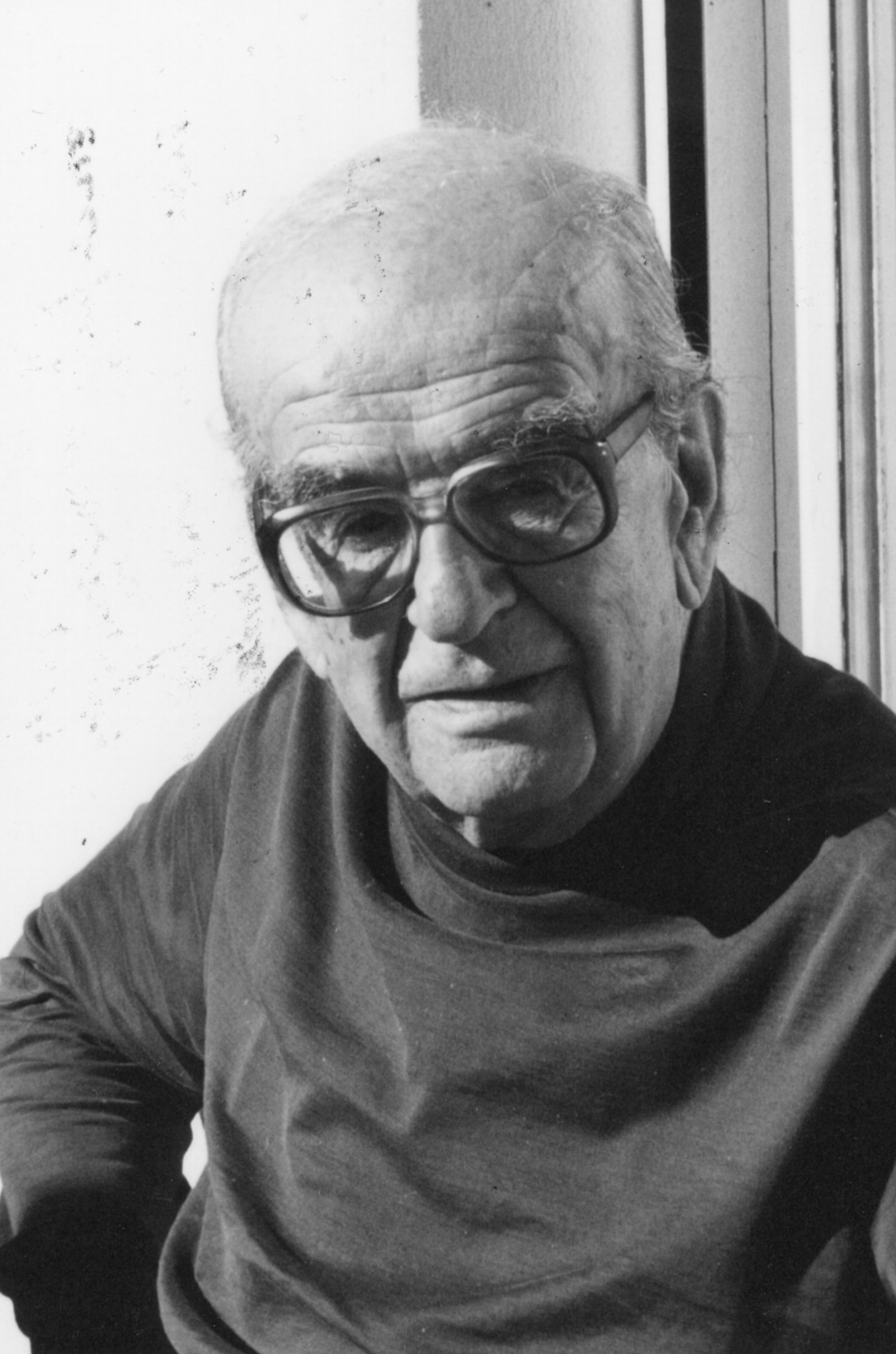

Ernesto Grassi: Frases en inglés

Fuente: Rhetoric as Philosophy (1980), p. 77

Fuente: Rhetoric as Philosophy (1980), p. 40

Fuente: Rhetoric as Philosophy (1980), p. 32

Fuente: Rhetoric as Philosophy (1980), p. 40

Fuente: Rhetoric as Philosophy (1980), p. 28

Fuente: Rhetoric as Philosophy (1980), pp. 18-19

Fuente: Rhetoric as Philosophy (1980), p. 39

The fundamental argument of Plato’s critique of rhetoric usually is exemplified by the thesis, maintained, among other things, in the Gorgias, that only he who "knows" [epistatai] can speak correctly; for what would be the use of the "beautiful," of the rhetorical speech, if it merely sprang from opinions [doxa], hence from not knowing? … Plato’s … rejection of rhetoric, when understood in this manner, assumes that Plato rejects every emotive element in the realm of knowledge. But in several of his dialogues Plato connects the philosophical process, for example, with eros, which would lead to the conclusion that he attributes a decisive role to the emotive, seen even in philosophy as the absolute science.

Fuente: Rhetoric as Philosophy (1980), p. 28